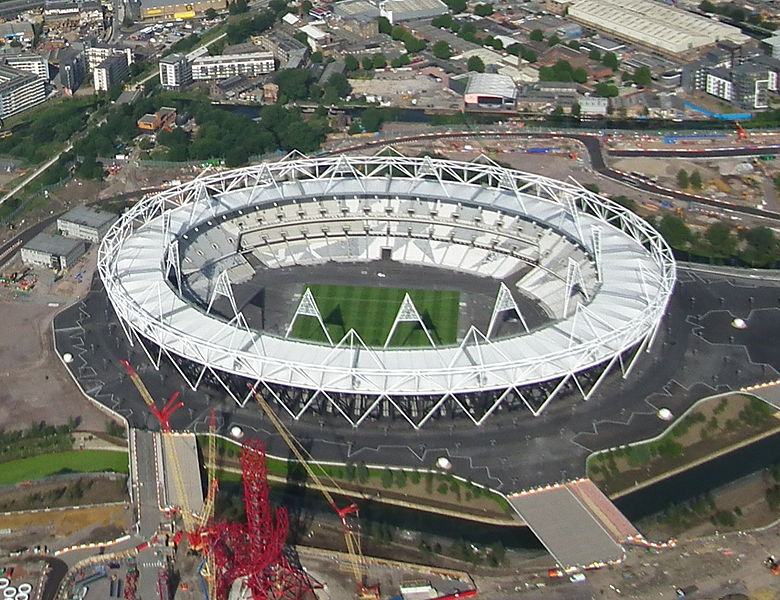

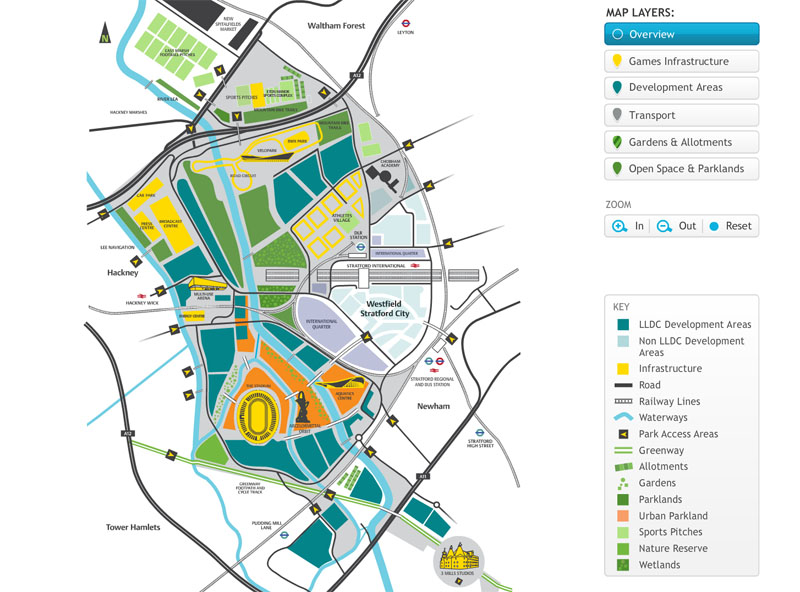

A key aspect of the plan was the creation of new, predominately residential, neighbourhoods surrounding the park. We designed a number of these (thirteen permanent and fifteen temporary bridges) as part of a suite of supporting infrastructure components for the park.Īs the Games approached, we began leading an additional strand of work developing the Legacy Masterplan to guide the park's maturation into a permanent piece of London. Key to the park's success has been the construction of a significant number of bridges to, in Games mode, accommodate the large crowds and facilitate connectivity across the site and in legacy mode, to permanently stitch it into the fabric of the city. The remaining venues were designed as temporary facilities and dismantled post-Games. These each maintain a relationship with the park and the surrounding urban areas. Of the primary sporting venues, just four were retained - the Stadium, Aquatics Centre, Handball Arena and Velodrome. In this way, a landscape designed initially to accommodate large numbers of people at a global event evolved into today's Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, and amenity for the local communities that line it. After the Olympics, the extent of the concourse was substantially reduced, replacing much of the previously paved area with planting. The scale and configuration were developed principally in response to anticipated visitor numbers, up to 250,000 people during the busiest days of the Games. The park was planned across two discrete topographical layers: a lower level defined by the waterways that meander through the site and an upper level defined by the platform of the public concourse on which various venues were constructed. It followed the landscape and was threaded with waterways. The pattern was like that of the previous Games in Beijing, but the London concourse was substantially smaller, and more organic in form, respecting the found topography. Around these were the temporary structures that fed and supported the Games. In the centre of the park was a wide public concourse. The River Lea offered the prospect of a continuous footpath and cycle path linking the city with its rural hinterland - the first of its kind in London.Īt the heart of the plan was a very simple diagram. A similar opening-up was possible in the north-south direction.

#London olympic park address series#

A key aspect of the Olympic plan was, therefore, to initiate a more complex and comprehensive network of connections across the valley - including a series of new bridges - which in turn provided the framework for legacy development following the Games. The series of trunk roads that cross the site from east to west contrasted, prior to the Games, with only one east-west local road. Ironically, the more its roads and buildings were configured to fulfil this role, the more fragmented the local infrastructure had become. In effect, it acted as London's backyard, with bus depots, stabling for underground trains, sewage treatment works, gasworks, power generation and transmission facilities, railways sidings, warehousing, goods distribution, urban motorways, waste storage and waste treatment, all neighbours to a significant group of eighteenth-century mill buildings immediately to the south of the site. The River Lea's low-lying, marshy and flood-prone valley was difficult to bridge or develop, so over many years, the site had become the location for many of those essential back-of-house functions needed to sustain the growing metropolis. It was thus essential that the Olympics be planned in an efficient and sustainable way whereby venues and infrastructure could have a useful life long after the Games, avoiding the expensive white elephants that have mired the experience of some other host cities.

So, the Olympic Games were to be a catalyst for a much larger project of urban change. Many of the areas around the site has some of the UK's highest areas of deprivation and there had long been a desire to redress this imbalance.

In a wider strategic context, the project was an opportunity to bridge long-standing inequalities between west and east London. Indeed over the course of the Olympic Games more than 85% of visitors arrived at the park by rail. Today, the station connects three tube lines, two National Rail lines, the Docklands Light Rail, Overground and Eurostar services. One surprising asset of the site, even before the Games were ever planned, was the quality of its neighbouring railway connections thanks to the proximity of Stratford Station. Here, the River Lea, which flows south into the Thames, had long formed a divide separating the body of the city from its eastern extension. The location was an elongated site in the Lower Lea Valley at Stratford in east London.

Our work began in 2003 as one of a team of four consultants who developed a masterplan for a new Olympic Park for London's successful bid to the International Olympic Committee to host the 2012 Games.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)